Feast of the Stigmata of Saint Francis: Marked with the Wounds of Christ

On September 17, Franciscans celebrate the Feast of the Stigmata of St. Francis, to recall Francis's body being wondrously marked with the wounds of Christ.

What happened in La Verna?

A modern biographer, Andre Vauchez, says: "What happened on La Verna on an undetermined day in September 1224?. . . It is difficult to say with any precision, as Francis [himself] did not mention it in his writings, and he forbade from speaking about it those rare persons who came to observe the traces of the wounds. It is thus only after his death and before his burial that a certain number of witnesses were able to actually see them on his flesh."

Context of the Stigmata

We do know the setting. By 1224 Francis's health was rapidly failing, yet in late summer he decided to make an arduous journey from Assisi to a favorite hermitage on Mount La Verna in Tuscany. His purpose was to go apart at this critical stage in his life with a few companions to observe the "Lent of St. Michael" — a forty-day retreat devoted to prayer and fasting from the Assumption to the feast of the Archangel. This particular day, Francis had gone apart from the others to meditate more intently on the Passion of Christ when something happened.

This painting by Spanish artist José Benlliure y Gil (1855–1937) depicts St. Francis and Brother Leo in a cave at La Verna.

Classic Account of the Stigmata

The account provided by St. Bonaventure in his official life of 1260s, in turn based on the 1229 account in the first "Life of Saint Francis" by Thomas of Celano — only three years after Francis's death — became normative in the Franciscan tradition:

While he was praying one morning on the mountainside around the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, he saw the likeness of a Seraph, which had six fiery and glittering wings, descending from the grandeur of heaven. . . to a spot in the air near to the man of God. The Seraph not only appeared to have wings but also to be crucified. His hands and feet were extended and fastened to a cross. . . . Seeing this, Francis was overwhelmed. His mind flooded with a mixture of joy and sorrow. He experienced an incomparable joy in the gracious way Christ appeared to him so wonderful and intimate, while the deplorable sight of being fastened to a cross pierced his soul with the sword of compassionate sorrow. He understood . . . that such a vision had been presented to his sight, that he might learn in advance that he had to be transformed totally, not by a martyrdom of the flesh but by the enkindling of his soul, into the manifest likeness of Christ Jesus crucified. The vision. . . inflamed him interiorly with a seraphic ardor and marked his flesh exteriorly with a likeness conformed to the Crucified; it was as if the liquefying power of fire preceded the impression of the seal. . . . the likeness of the Crucified in his side as well as in his hands and feet. . . . And so the angelic man, Francis, came down from the mountain bearing the likeness of the Crucified, depicted not on tablets of stone or on panels of wood, but engraved on parts of his flesh by the finger of the living God. (Bonaventure, Minor Legend, 6)

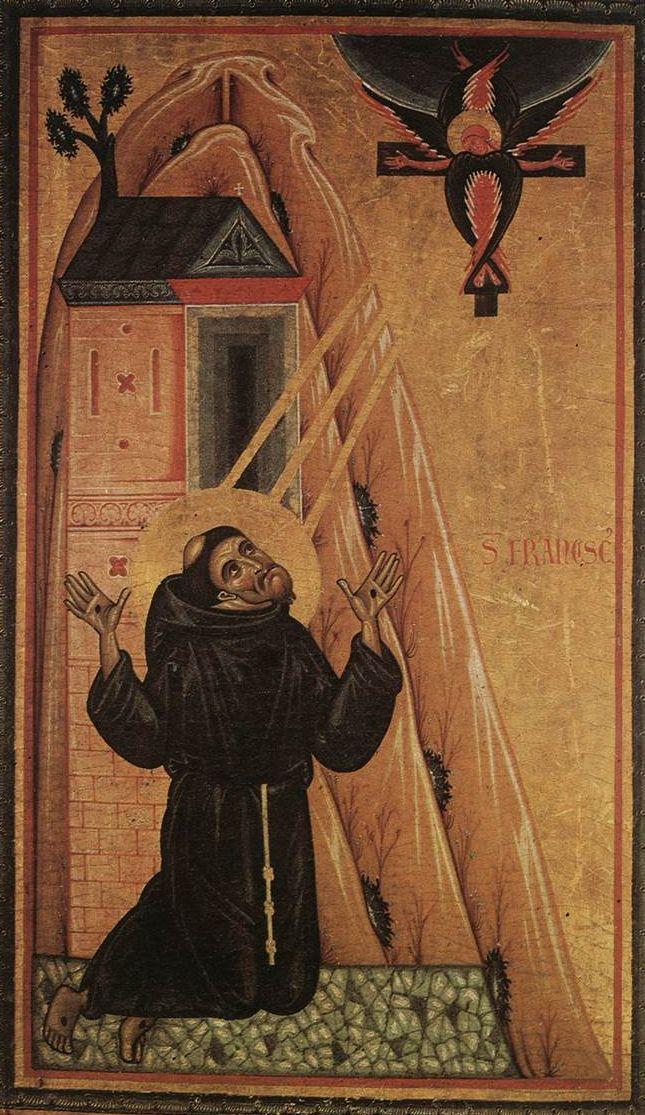

Giotto, Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (detail), Italian, c. 1295–1300, Paris, Musée du Louvre. This image was based on St. Bonaventure's account.

Meaning of the Stigmata

It is clear that here Bonaventure, following Celano, is not giving a matter-of-fact account but presenting an experience in theological terms, incorporating Biblical symbolism: the image of a Crucified Man enfolded within the wings of a six-winged Seraph weaves together three Biblical references: John 3:13-17 (the Son of Man being lifted up, giving his life for the salvation of all); Numbers 21:4-8 (the Old Testament account of the saraph serpents as an image of healing); and Isaiah 6:1-2 (the six-winged Seraphim standing before the presence of God}. This powerful symbol, however, packed a simple but overwhelming message — as Ilia Delio puts it in her Franciscan Prayer, Francis came to understand that his experience of God would reach its fullness only "by allowing himself to be fully grasped by the compassionate love of the crucified Christ. For the sake of love he spared nothing and gave everything he had to the one he loved."

This image by Master of San Francesco Bardi from the second quarter of the 13th century is one of the earliest depictions of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata.

The Stigmata: from without or from within?

In his recent study, Francis of Assisi: His Life, Vision and Companions (London: Reaktion Books, 2023), Michael Cusato offers a profound suggestion:

What is the meaning of this complex image presented to us [in the sources]? First, most commentators interpret the image as being that of a Seraph angel who then proceeds to imprint the five wounds of Christ’s passion into onto the praying Francis. But this is inexact. The central image is indeed the Crucified Christ presented as lifted up. . . The Seraph, in other words, is not really an angelic figure; rather it is Christ himself, crucified for the healing of the human race. Hence, the central figure is Christ Crucified enfolded within the wings of an angel. . . the very person on whom Francis had been so profoundly meditating. . . . Second, such artistic representations — as moving as they can be — can also be unwittingly misleading. For such as depictions appear to show an angel zapping, as it were, the praying Francis in the same five points of his body, replicating the wounds of Christ Himself on the cross. . . However, my contention is the following: what occurred in this mystical rapture was that Francis had internalized so deeply and profoundly the image of the Crucified Christ on the cross that it literally, physically, exploded out of his psyche and onto his own flesh, marking him with the wounds of Christ, the stigmata. Hence, rather than the mystery being conceived as a movement from outside of Francis and onto him, the movement went, rather, from within him and out onto his own body. So powerful was his prayer and so visceral was his internalizing of the mystery of Christ’s healing grace from the cross for the world that it made its way onto his own body. The stigmatization was, in other words, the paradigm of a psychosomatic experience. . . Francis became what and to whom he was praying.” (Michael F. Cusato, pp. 181-182)

Stigmata (2020), Michael Reyes, OFM, paper, metal leaves, marble dust and oil on canvas 72” x 60”. St. Bonaventure University, New York.

La Verna Today

La Verna remains an important place of prayer and retreat today. Click here to visit the website of the La Verna Franciscan friar community.

View of the rugged mountainside of Mount La Verna on which the sanctuary of the Stigmata stands (Photo: Mattana, Wikimedia Commons).

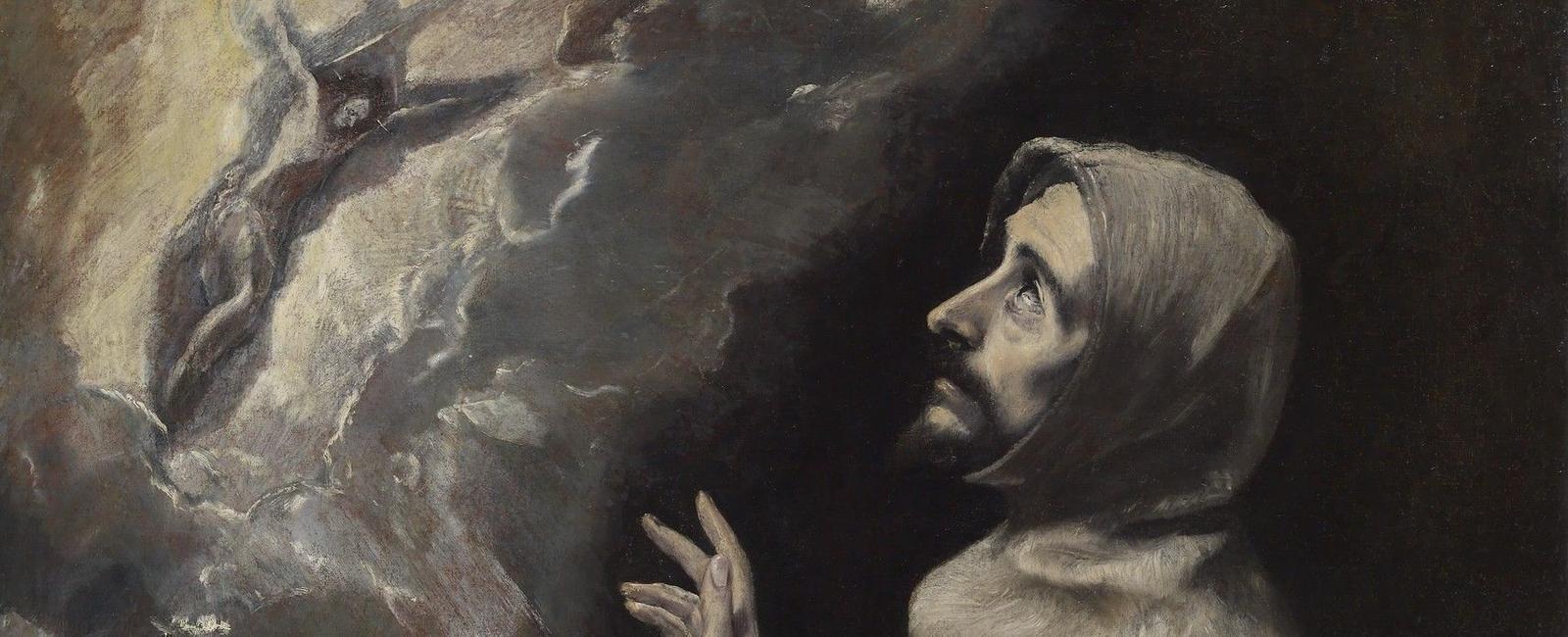

Main image: El Greco, St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata (detail), Greek, 1586-1600, Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery. El Greco was a Secular Franciscan and the Stigmata was one of his favorite subjects.

Dominic Monti, OFM

Professor of Franciscan Research in the Franciscan Institute of St. Bonaventure University

Dominic V. Monti, OFM, is a Franciscan Friar of Holy Name Province (USA) and currently professor of Franciscan Research in the Franciscan Institute of St. Bonaventure University. He devoted the greater part of his ministry to teaching the History of Christianity, in particular the history of the Franciscan movement. He has contributed two volumes to the Works of St. Bonaventure series and is author of Francis & His Brothers, a popular history of the Friars Minor.